In December 2019, filmmakers Justin Krook and Luke Mazzaferro were flying around Australia to promote a documentary they'd made about the future of artificial intelligence when they began to notice a troubling, and recurring, sight far below them.

"We kept looking out the window and saying to each other, 'What the hell is going on?'" Mazzaferro, a Sydneysider, recalls.

Travelling up and down the eastern seaboard, their view was increasingly one of enormous smoke plumes peeling away from ever larger swathes of charred, scarred landscape.

"We were well aware of the fires that had been raging for months already, but then seeing the scale of it all from the sky was deeply unsettling," he says.

A couple of months later, the pair was invited to hear a long-time member of the NSW Rural Fire Service (RFS), Andrew Flakelar, share his frontline experiences of a winter, spring and summer like no other.

Over the course of the 2019-20 bushfire season, 33 people, including nine firefighters, lost their lives, 3094 homes were destroyed and more than 17 million hectares of land was burnt.

Listening to Flakelar, the filmmakers realised they may have stumbled upon the subject matter for their next documentary.

"It was the first time we got a real sense of the humanity behind the fires, as opposed to what we were just seeing on the news," Mazzaferro says.

Krook, an American who has spent much of the past four years living and working in Australia, was astonished to learn that 90 per cent of Australia's firefighters - some 170,000 people - are volunteers.

"Justin was like, 'Wait, hold on - what the hell?'" Mazzaferro laughs.

"That was actually the lightbulb moment when we decided to make this film," Krook says from his base in LA, having flown back to the US mid-year.

"We have volunteer firefighting forces here in California as well, but the scale and level of what Australia has, and how much it's relied upon, is incredible," he says.

From the beginning, Krook and Mazzaferro were inspired to focus on individuals and communities affected by the fires, including firefighters, rather than the fires themselves.

"Most of the stories in the film are happening after the fires went out and the rains came," Krook says.

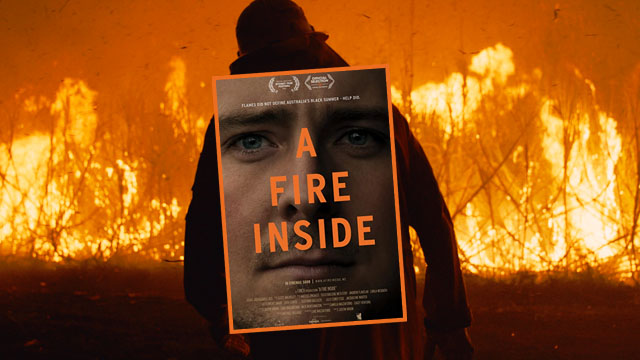

Even so, the first half hour of their feature-length documentary, A Fire Inside, plunges the viewer into the eye of the firestorm as various subjects give frequently terrifying first-person accounts of their experiences.

And while the pair didn't want to make a film about climate change, there are meaningful contributions from a meteorologist and an Indigenous fire practitioner about what we're getting wrong and how we can fix it.

Crucially, Krook and Mazzaferro were also keen to hone in on those kind souls and organisations that swung into action to help those whose lives had been turned upside down.

"It really was an impossible process getting it down to 10 or 15 characters whose stories we felt we could entwine, because everyone was affected by the fires and everyone had a story," Krook says.

Pandemic restrictions forced the filmmakers to limit their scope to NSW, but given the state recorded 2439 homes destroyed and 5.3 million hectares of land burnt, they weren't exactly hamstrung.

Mazzaferro adds that by focusing on just a handful of townships, they were able to capture "that lovely, intertwined, small community feel, which I think is emblematic of the story at large".

One of the central subjects is Nathan Barnden, a young, volunteer firefighter with Jellat RFS brigade in NSW's Bega Valley.

On New Year's Eve 2019, he risked his life to enter a burning house and rescue a grandmother, her daughter and three grandchildren.

Barnden went on save the lives of 13 people over the summer.

Nevertheless, he became wracked with guilt that he couldn't save his uncle and cousin, who had perished while trying to defend their home not far from where he saved the grandmother and her family.

"We came across Nathan in our initial research as he had already had media attention," Mazzaferro says.

"By that point it was six months on, so he was in a very different place from having cameras pointed in his face right after the fires.

"Still, it took a while for him, and especially his family, to agree to talk to us and build that trust."

Adds Krook: "the fires went on for months and months. People like Nathan lost family members and then laced up their boots and went back out and volunteered".

As the documentary progresses, it becomes clear that Barnden is not alone in having struggled to process the trauma he experienced.

Another firefighter, Balmoral RFS captain Brendan O'Connor, reveals the significant toll the bushfires took on both his marriage and mental health.

The NSW Southern Highlands township of Balmoral suffered heavy damage on December 21, 2019, with 20 houses lost and an estimated 90 per cent of the area's trees burnt.

It's a theme picked up by Commissioner of Resilience NSW Shane Fitzsimmons, who was chief of NSW's RFS during the 2019-20 bushfire season.

"There is this stigma or shame about being emotionally impacted or affected," Fitzsimmons says in the film.

"I would plead to everybody, and particularly our men - not exclusively, but men are the worst offenders in my experience - we've got to do more to open the doors and give permission to our mates, our colleagues, our families, our loved ones, that it is OK to be impacted and affected by traumatic experiences," he says.

Krook and Mazzaferro have received positive feedback from firefighters who have watched the film.

"They've told us that seeing people like Nathan and Brendan be so honest and open about their emotional state has helped themselves recognise they also need help and given them the courage to raise their hand," Mazzaferro says.

In several cases, the filmmakers stumbled upon subjects by happy accident. Paula Zaja, who runs a community pantry and food rescue service in Bargo near Balmoral, is one of them.

"We'd just been to Balmoral and were driving through Bargo to see what their RFS station would look like on camera," Mazzaferro says.

"Out of the corner of our eye we saw a sign that read 'Our Community Pantry'. We went in and said we were making a documentary about the fires, and Paula said, 'I've got some lasagne coming out of the oven, do you want lunch?' That started our relationship with Paula," he says.

At the height of the fires and during recovery last year, Zaja's service was helping feed 4000 families.

"We had volunteers providing food for our volunteers who were providing food for our firefighters," Zaja says in the film.

Another lucky find was pensioner Barbara Stewart, whose Nerrigundah home was destroyed by fire, leaving only her beloved red-brick fireplace and chimney. Alas, for insurance reasons, it had to be toppled.

Forced into makeshift accommodation on her property in the aftermath of the fires, she was eligible for one of 200 temporary accommodation pods provided by the Minderoo Foundation.

Yet in the film Stewart sees fit to donate her pod to a neighbour whom she feels needs it more.

These quiet acts of altruism illuminate the strength, resilience and connectedness of small rural communities.

Mazzaferro hopes the film encourages viewers to realise that everyone can make a difference in their community, especially when the chips are down.

"Individual actions can go a long way," he says.

"It's not just the firefighter who rushes towards danger when everyone else is fleeing.

"It's the Paulas of the world who are providing basic human needs like a hot meal, or the selflessness of someone like Barbara, donating her pod to another family."

A Fire Inside screens at Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre on Saturday and is on-demand from Friday to November 21 as part of the Sydney Film Festival.

For more information visit sff.org.au

Lifeline 13 11 14

beyondblue 1300 22 4636

© AAP 2021

Image: Film still, A Fire Inside; IMDB